Last February, the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter started a two-year journey to provide the first detailed pictures of the sun’s poles and insights about the never-before-observed magnetic environment that regulates the sun’s 11-year solar cycle. But how can a satellite move around the sun without burning? Here Samir Jaber, content writer at materials search engine Matmatch, explores the materials that protect a solar orbiter.

Of the famous six European-built spacecraft, including the Ulysses, SOHO, and Cluster missions, the new satellite from ESA and NASA will fly the closest to the sun at a distance of 42 mil km, just over a quarter of the distance between the star and our planet and well inside the orbit of Mercury. The mission will last seven years, and by the end of 2026, we should have close-up pictures of 180 km-wide solar landscapes to explore why glowing gas forms loops in the strong magnetic field.

The Solar Orbiter measures 3.1 m x 2.4 m and carries a scientific payload of ten different instruments, weighing a total of 180 kg. Of these ten instruments, six are remote sensing, like imagers and ultra-sophisticated telescopes, which can be used to see the sun from a distance. The other four instruments are fixed to the Orbiter, measuring the environment surrounding the spacecraft, including the solar wind plasma and the electric and magnetic fields.

The Orbiter’s journey is going to be challenging because the spacecraft is exposed to heat 13 times more intense than that on Earth. Even more dangerous, at its closest approach, 26 mil miles from the sun, the spacecraft will need to resist eruptions and explosions of energy caused by magnetic forces called solar flares.

The sunshield

The solar orbiter is designed to always face the sun, so it is equipped with a sunshield for protection. This sunshield, also known as the heat shield, has the shape of a 3 m x 2.4 m sandwich with a thickness of 38 cm.

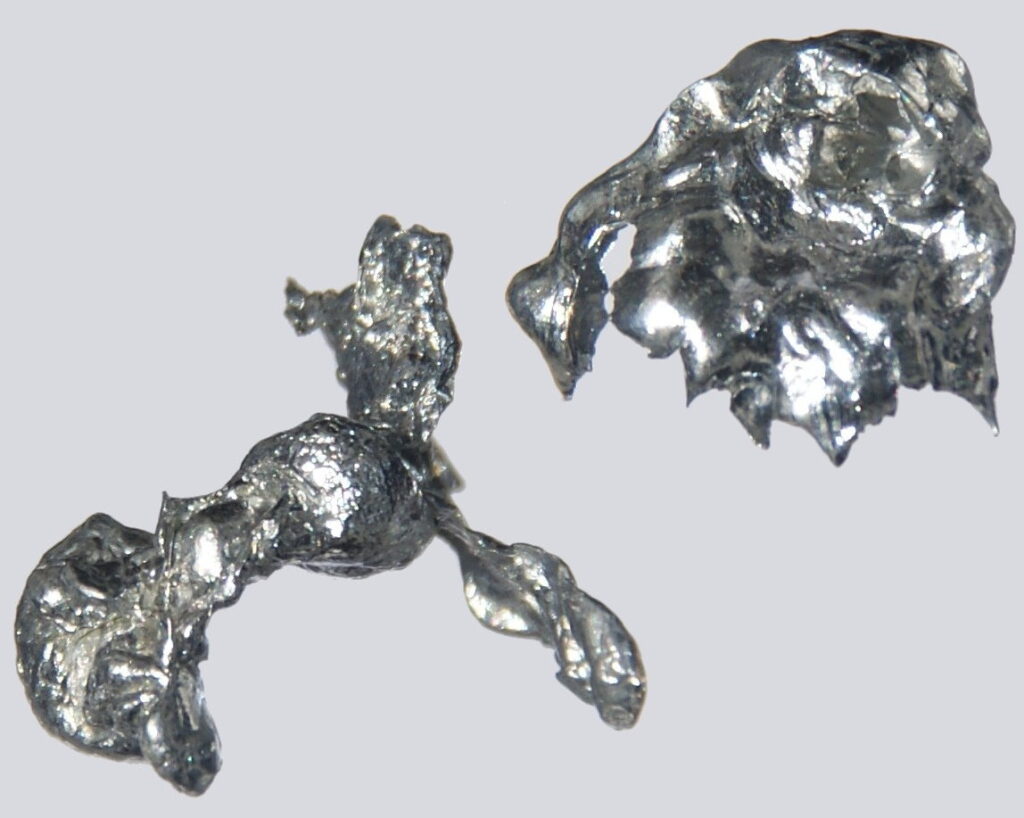

As the spacecraft needs to resist temperatures up to 600ºC, the selected materials are titanium and aluminium. The surface of the spacecraft is covered with titanium foils, as they can effectively reflect heat. The middle part is empty to disperse the radiations away, while inner layers of aluminium are used to insulate the inside and help the spacecraft maintain a normal temperature.

Coatings

To make the titanium foils more heat resistant, materials engineers created two special coatings: SolarBlack and SolarWhite.

SolarBlack and SolarWhite were developed by the mechanical engineering company ENBIO, in collaboration with ESA and Airbus Defence & Space. The black calcium phosphate that makes up SolarBlack gives this coat the property of high emissivity and high solar absorbance, helping to mitigate extreme solar radiations. SolarWhite, meanwhile, is an inorganic coating that handles electrical conductivity better and can help the orbiter prevent electrostatic discharges.

Both coats can be applied to metallic substrates, including titanium, aluminium, copper and steel.

Materials search engine

For engineers, these coatings breathe new life into existing materials, which renders the likes of titanium, aluminium and other materials more resistant and functional in many new applications.

Today, it’s much easier for materials engineers to find the right information about existing materials. They can use Matmatch’s database to find more than 26,000 materials and learn more about their properties at a touch of a button. As searching is fast and easy, materials engineers can come up with new ideas, find global materials suppliers, and work on their projects without delay.

If a spacecraft can move around the sun today without burning, it is because of materials engineers, manufacturers and other experts who know how to bring innovation into existing and new materials. This process can be applied not only to astrophysics, but also for any scientific and engineering endeavor.

This article was featured in Electronic Specifier, Design World, and Design, Products, & Applications.